The Market Equilibrium Fallacy Part 1

January 6, 2022 10 minutes • 1948 words

Table of contents

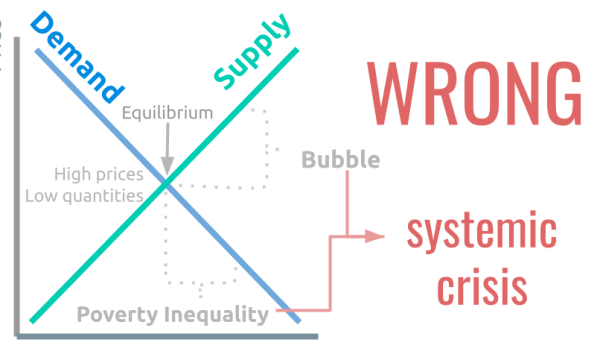

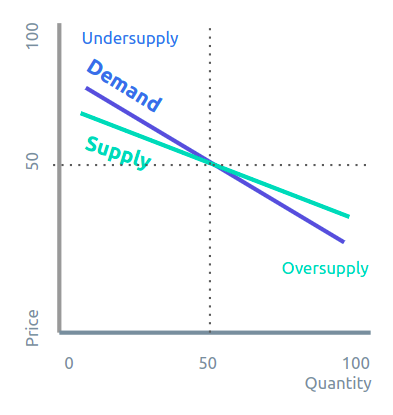

The biggest fallacy of Economics is Market Equilibrium which is taught in basic economics or ‘Econ101’ everywhere as the supply and demand curve forming an ‘X’ and meeting in a state called ’exact equilibrium’.

Adam Smith exposed this as mercantile sophistry in the 18th century, then called the ‘balance of trade’. To prove that this idea of ‘balance’ is the same in essence with the ’equilibrium’ of economics, let’s compare the essence of both ideas.

The Law of Demand

Samuelson’s Version

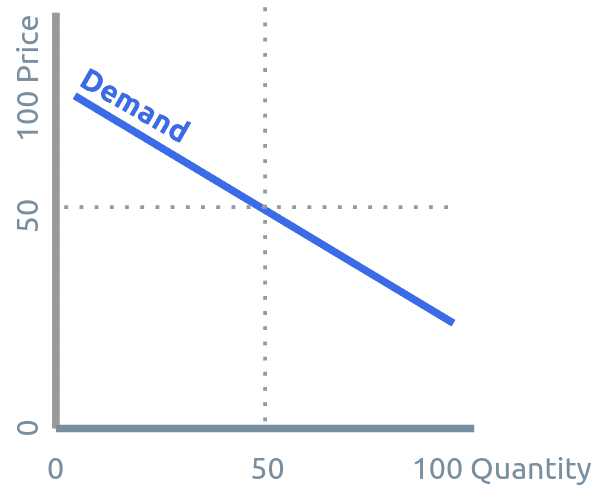

Modern Economics began with Paul Samuelson’s neo-classical synthesis which described a downward sloping picturization of the ‘Demand Schedule’*. It means that the price of a thing goes down the more abundant it is:

*Instead of a demand schedule, Supereconomics uses the Economic Table of the Physiocrats to determine the real price of everything in real-time. If everyone knows the real price of everything, then information asymmetry and profit maximization stop existing. Consequently, economic crises no longer have a chance to form. The maxim ‘prevention is better than cure’ applies to an economy just as it applies to health.

Samuelson then goes through a few more paragraphs to prove this.

Smith’s Version

Smith uses only 4 sentences to explain this from the viewpoint of an impartial spectator (not as a buyer nor seller):

Like Smith, Samuelson also gives the example of water.

However, Samuelson’s version observes this phenomenon from the viewpoint of business or the supplier first instead of the buyer or demander. This is important because in reality, the buyers are made up of people in society. This subtle fact might not catch the attention of a casual reader, but it can be seen by a Socratic dialectician (a person who has realized the True Nature of Existence).

The Mercantile Version

Smith points to Thomas Mun’s England’s Treasure on Foreign Trade as the origin of equilibrium, so we look for Mun’s version of the demand curve.

Plotting this, we get the same downward sloping demand curve. We thus prove that Samuelson, Smith, and Mun agree on a downward sloping demand curve:

Digression on the ‘Law’ of Demand: Creating the non-problem ‘paradox of value’ to justify the fallacy called Profit Maximization

Feb 2017

Many economists, including Samuelson, cite Smith’s example as a 'paradox of value', where in fact, there was never a paradox to Smith. Anything that is difficult to obtain yet desired by the mind, such as diamonds, simply will naturally have a higher price than that which is easy to obtain, like water. Economists create a paradox in order to justify the creation of the concept of marginal utility to ‘solve’ the paradox. This marginal utility requires the quantification of pleasure or utility, which is then ‘maximized’ as ‘profit maximization’ -- the second key fallacy being perpetrated by Economics.

By destroying the paradox of value, then value is properly kept as subjective instead of being objectified into numerical increments. This will then make profit maximization lose its top importance in the minds of businessmen and people in general. This then will make businessmen, investors, and entrepreneurs shift their focus on the actual non-numerical, non-quantifiable benefits that their businesses create.

The Supply Curve

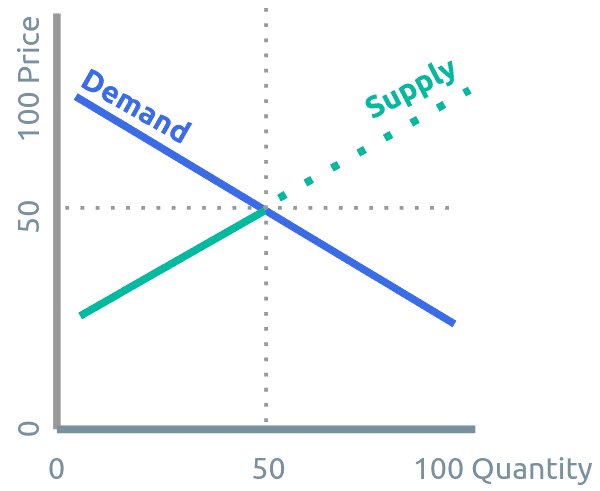

We see that the demand curves of Smith the moralist, Samuelson the businessman, and Mun the merchant are the same.

Samuelson’s Version

Next, we look at the Samuelson’s Supply curve to see that it is also business-first:

Samuelson says that suppliers react to society’s high demand for a product (which manifests as higher prices), which then motivates them to produce more of that product. Because of natural limitations, the costs of producing each additional product eventually increase and this leads to higher prices at higher quantities.

In this version, the main cause for the rise in prices with rising quantity is the rising cost of production. Thus, we will call this the manufacturer’s version of the supply curve.

The Mercantile Version

In Englands Treasure by Foreign Trade , Mun describes the mercantile supply curve:

Unlike the manufacturer’s supply curve which rises because of rising supply-side production costs, the mercantile supply curve rises because the increased denand-side sales also increases the competition between the merchants for the supply-side wholesale goods.

While Samuelson’s supply curve will lead the producer to want to own all the land, the curve of Mun will lead the merchant to want the collapse of all other merchants. The perfection of the former is done through a war for territory as seen in World War I and II, while that of the latter is done through a trade war, best seen in the War of Jenkin’s Ear (Update Sept 2021: and also by Trump’s trade war with China).

This mercantile supply curve is also seen in modern economics textbooks as the “ultra-short run supply curve” which is based on profits instead of costs. Samuelson seems to downplay the profit motive in order to emphasize the law of diminishing returns, whereas modern textbooks seem to go straight for profits.

Smith’s version

Smith’s supply curve can be seen in Book 1 of The Wealth of Nations, and like Samuelson, is based on cost and not profits.

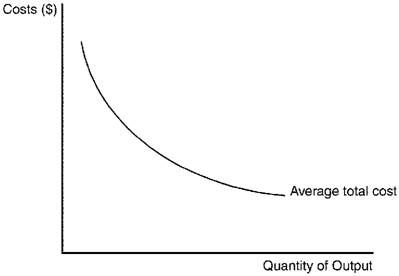

Unlike the producer’s or mercantile supply curves which slope upwards, Smith’s supereconomic supply curve slopes downward to represent less effort and energy expense while production increases. This phenomenon is called economies of scale or division of labour.

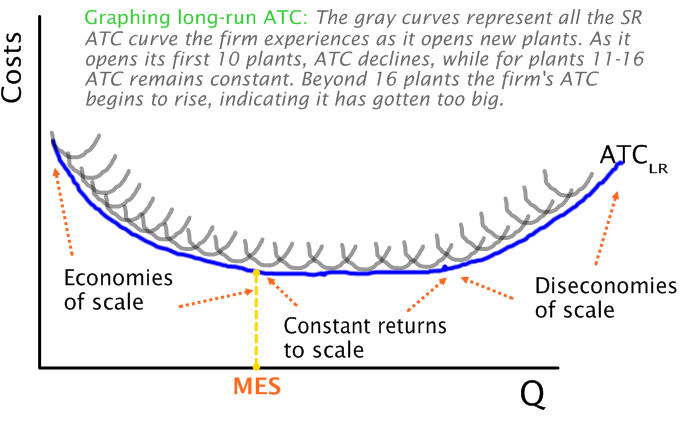

Why does Samuelson’s costs go up with more production, while Smith’s costs go down, properly leading to lower prices? This is simply because Smith and Samuelson’s costs are seen from different positions:

Smith’s supply curve is in the left side sloping downwards, representing efficient production, while Samuelson’s is the one on the right, representing diseconomies of scale or when the production is being forced beyond its natural rate or limits.

All Economics books that discuss the upward sloping supply curve have no choice but to admit that it is caused by inefficiency:

The Supply Curve of Economics is Wrong (Unnatural)

This admission means that the upward sloping supply curve is unnatural.

If a company is unable to supply the needs of its customers, then other companies can enter and address those needs, relieving the original company of the need to produce unnaturally and inefficiently.

Therefore, the upward sloping curve can only be true if the company had a monopoly and could charge high prices at higher quantities. This means that both the mercantilist and manufacturer’s supply curves exist only in a non-free world, or one that follows a survival-of-the-fittest doctrine, which Smith explains simply:

Thus, we see that the supply curve of modern economics, first established in the 1870’s in Europe and then globally through Samuelson, unnoticeably establishes the idea of monopoly, war, and trade war as a natural state.

In reality, the natural supply and demand curves both slope downwards, representing a single human society as shown below.

The next post will explain the unified natural supply and demand curves.